NEWS

NEWS

Published

Dr Moritz Ege (Principal Investigator for the University of Zurich research team) writes about the Swiss electorate supporting a popular initiative for increasing pension payments, asking whether the vote marks a new era of redistribution in Switzerland.

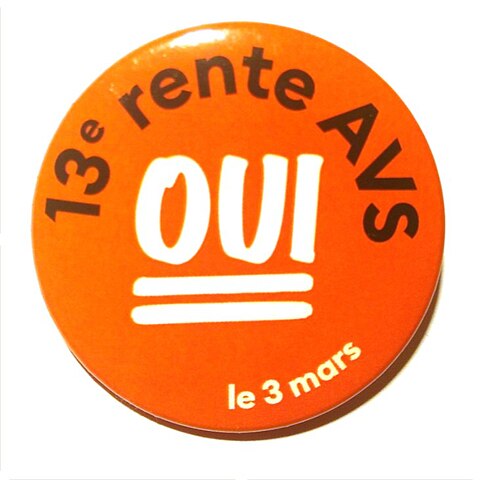

Four months ago, Switzerland experienced a political earthquake in the field of redistribution. On March 3, 2024, 58% of Swiss voters who went to the polls voted for a popular proposal (Volksinitiative) that will increase yearly payments to pensioners by 8.33%. Following this vote, the old age and survivors’ insurance, AHV (Alters- und Hinterlassenenversicherung), will be raised by one twelfth of the annual pension, creating a “13th monthly payment” for almost all Swiss pensioners and helping future beneficiaries of this insurance keep up with rising costs of living. In a time of neoliberal reforms, austerity, and welfare state retrenchment throughout Europe, this was surprising news – especially in a country with a solid right-wing majority and a strong liberal orientation in matters of political economy. On the Swiss political left, the result was celebrated as a watershed moment in history: for the first time ever, the electorate had voted for a popular proposal that directly expands the Sozialstaat, as the welfare state is known here. The left-wing weekly Wochenzeitung (WOZ) wrote that “no superlative seemed out of place” in the days after this result. It quoted an enthusiastic labour union activist: the vote could have a “social policy effect like the 1918 general strike”.

Will this vote, then, usher in a new era of redistribution in Switzerland? Or is it merely an isolated and ultimately small step that goes against the current of a much broader movement that prioritizes the demands of capital? And what, if anything, does this have to do with the digital – or, taking into consideration the questions that initially inspired the ReDigIm research project, with political-economic and cultural shifts during and after the Covid pandemic? In what follows, I will briefly contextualize this political event and sketch out some answers to these questions.

For understanding the sense of wonder that pervaded the public, it is important to note that previous expansions of the social safety net in Switzerland had come about by other ways, usually government-led, not through popular initiatives, i.e. ballots called for from outside the government. The establishment of the AHV in 1946/47, for instance, was formally initiated by federal law and then supported in an ex-post popular vote (over 80%). More often than not, the popular vote – be it through a majority of overall votes or the majority of cantons – had turned down proposals to introduce new social safety measures, such as parental leave or a cap on health insurance premiums. Across the decades, a majority of Swiss voters has tended to cast their lot with capitalist growth, rather than redistributive policy. At the same time, it must also be noted that the popular vote supported the AHV system against attempts to increase retirement age, especially that of women (which for a long time was 64, with men retiring at 65; this ‘fortress’ fell, however, in 2022). Nevertheless, if anything in Switzerland comes close to the standing that the National Health Service has in the United Kingdom, as a much-beloved collective achievement, it is the AHV.

For us as researchers on redistributive imaginaries in an era of digitalization, the success of the popular initiative “for a better life in old age (for a 13th AHV pension)”, as it was officially titled, was also remarkable. The AHV is the strongest top-to-bottom redistributive instrument in the Swiss social security and welfare system – which is itself a hybrid of liberal, corporatist-conservative and (less prominently) social-democratic elements. Whereas the second and third “pillars” of the Swiss pensions system, which were introduced in the 1970s and 1980s, consist of individual tax-exempt (and, in the case of the second pillar, employer-supported) accounts, the AHV as “first pillar” is a (capped) pay-as-you-go system. High earners pay in much more than they are allowed to take out. The payments that the AHV gives to pensioners are primarily covered by current workers’ paycheck deductions, matched by employers, and to a smaller extent by taxes and other state income. Arguably, in the current era of financialization, a further, indirect, but nevertheless crucial redistributive effect of pay-as-you-go-systems like AHV is that they do not redistribute to the banking and insurance industries (through fees et cetera), bypassing accumulation and the extraction of financial surplus.

Given all of this, if there is an imaginary at work in the AHV as a socio-symbolic entity, then it is probably one of labor-based (and to some extent patriarchal), national-universal, and efficiently bureaucratic redistribution – solid, limited, unsexy, reliable. The framing as a “13th monthly payment” was fittingly chosen here: most Swiss employees receive a “13th salary” in November or December as part of their regular pay package. In using this frame and activating those meanings, rather than, say, calling for an 8.3% raise of pensions, campaigners evoked a model that is known to most people from the remuneration they – by contract – receive for their labour, rather than an arbitrary “handout”, which is often dismissed in meritocratic discourse.

What – beyond such semantic means – made the result in March 2024 possible?

On the one hand, there was a relatively high turnout as the left managed to mobilize its base, especially in urban and French-speaking areas. Observers, including some of our interviewees in digital companies, lauded the digital campaigning prowess of the left in this specific case. Equally important, and in a more classic sense of interest-based politics, many working- and middle-class voters who are usually loyal to the right-wing populist Swiss People’s Party (SVP) or the conservative Mitte, which is particularly strong in Catholic regions, this time did not follow the recommendation of the parties that they usually voted for. Instead, they seem to have followed their own economic interests. Political scientists and journalists debated whether this, then, was “the poor” winning over “the rich” or rather “the old” over “the young” – but in either case, 58% was quite a decisive win for a popular initiative. Business lobbyists and the liberal-conservative parties seem to have overplayed their hand and failed to hold their alliance together.

However, writing this in late June, a few months later, it seems that normalcy has returned to Swiss politics. Another left-wing initiative, which aimed at curbing health insurance costs for lower-income people, was dismissed decisively by voters in June. And an important decision is yet to be made: it remains unclear how the “13th month” will be paid for – the popular initiative left this question open. While the left basically wants employers to contribute, the right-wing majority suggests raising VAT. Clearly, redistributive politics remain contentious, and while the March vote may have been a success for the left, the latter will struggle to maintain its momentum.

This, then, can be read as an interesting story of direct democracy in the current crisis of neoliberalism.

For the ReDigIm project, I believe that two further points are of interest.

The first is that the Covid time – not only as a “real” event, but also as a discursive one – did indeed make a difference. In Switzerland, where there was an unusual level of state intervention to support “the economy” (including large companies) during the pandemic, the Overton window on redistributive policies has shifted. One result of ReDigIm’s work package 1, which examined media discourses on redistribution and the digital during and after the Covid pandemic, was that “redistribution” (Umverteilung) remained somewhat of a dirty word in Switzerland, especially in the German-language press, which almost unequivocally leans liberal-conservative. We were surprised that some commentators in the right-liberal flagship Neue Zürcher Zeitung, for instance, feared at the time that a dam had broken during Covid and there would be subsequent demands for redistribution, leading to a more “socialist” economic model. If the state bailed out businesses and provided a steady stream of income for many, and it sort of worked – where would this end?

About three years after these articles, this reasoning seems more plausible to us than it did at the time, as voters do indeed seem to have asked themselves similar questions and appear to have concluded that redistribution would benefit them and fit with their ideas of justice – without ruining “the economy”, as many economic liberals claimed. At the same time, this is not only about business – it also involves a broader and perhaps, normatively speaking, more problematic “moral economy”. We also observe that conservative and populist discourses according to which the state has in recent years done “too much” for refugees (notably Ukrainians) and migrants, and spends “too much” on foreign aid, also played a role here. Among some supporters of the initiative, there was a discursive strand in which “it was finally time to do something for us”, rather than merely for “others”. This wasn’t necessarily decisive – but it fits with the observation (especially in many Central and Eastern European countries) that in the late neoliberal conjuncture, support for classic redistributive policies has created alliances that are heterogeneous, contradictory, and probably also ephemeral – rather than foreshadowing a coming left hegemony.

The second observation concerns the role of “the digital” – or, rather, its lack of prominence in this case. To say that the digital wasn’t prominent isn’t to say that it was irrelevant: Surely, the popular initiative would have gotten less support without a well-run digital campaign. The AHV administration itself is not averse to the digital – individuals can look up estimates of the pensions they can expect online, for example (even if the private insurance companies have much fancier and contemporary-looking websites with more precise numbers). A digital campaign strategist also told us that they see a great potential that digital tools can help people who would benefit from supplemental, needs-based old-age payments – these are often not made use of because of untransparent rules and stigmatizing, bureaucratic procedures.

However, none of this should distract us from the basic fact that the digital did not figure prominently in the AHV campaign in a symbolic sense. What mattered here was not a primarily an imaginary of digitally-configured redistribution. Rather, it was about old-fashioned, state-led, bureaucratic redistributive social policy. Currently, however, redistributive effects of the latter dwarf those of practices like crowdfunding: the AHV pays out about 50 billions CHF annually; crowdfunding campaigns in the country amount to about 30 million, i.e. less than one thousandth. Even Swiss charities (Hilfswerke) are estimated to have received “only” 2.5 billion CHF in donations last year overall – about 5% of the sum the AHV works with. In our work on emergent redistributive imaginaries, we are probably well-advised to keep such matters of scale in mind.