NEWS

NEWS

Published

Based on findings from the first work package of ReDigIm, Dr Jonathan Paylor (Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Arts London) considers what the UK press coverage of recent surges in voluntary giving tells us about the ‘redistributive imaginaries’ being manifested in the context of digitalisation.

ReDigIm examines the ‘redistributive imaginaries’ that people draw on to make sense of different social mechanisms for redistributing economic resources. Having recently completed the first work package (a discourse analysis of newspaper articles from across the case study countries) we are beginning to get a sense of the imaginaries at play. Some of these have been discussed in previous blog posts from my Finnish and Swiss counterparts. This post reflects on findings from the analysis of UK newspaper articles (articles were drawn from five newspapers: Daily Mail, The Telegraph, Financial Times, The Guardian, The Mirror). In particular, I focus on representations of voluntary giving prompted by Covid-19 and the ‘cost-of-living crisis’ and consider what they reveal about the redistributive imaginaries being manifested in the context of digitalisation.

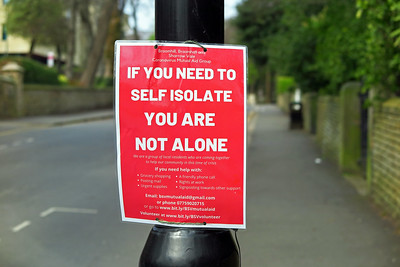

The ‘surge’ of voluntary giving driven by Covid-19 is a predominant theme across the body of texts we analysed. Along with the much-celebrated fundraising feats of Captain Tom, what appears to strike a chord with the press is the emergence of local networks of volunteers or ‘mutual aid’ groups who provide essential items to those in need. We see this for instance in a Daily Mail article which leads with the headline ‘The Corona Home Guard: Selfless, supportive and utterly inspiring’. Beyond its nationalistic overtones, what’s revealing about this article are the comments about the locals not waiting for ‘the Government to get the ball rolling’. Such statements are indicative of the value ascribed to ‘spontaneous’ and ‘organic’ bonds of affection and the ways in which a dynamic and creative civil society is set in opposition to a slow and unresponsive state. What’s further revealing about this article are the statements about the local group of volunteers communicating ‘via WhatsApp’ and operating like a ‘community Uber’. These statements are illustrative of how digital platforms are framed as enabling the creativity and dynamism of civil society and empowering people to deliver informal welfare.

We see similar meanings ascribed to voluntary giving in relation to the cost-of-living crisis. In particular, while the language is relatively downbeat compared to the celebratory accounts of fundraising during the pandemic, crowdfunding is represented as a tool that enables people to meet basic living costs by garnering community support. A Guardian article cites a GoFundMe spokesperson’s claim that ‘some of the stories are heartbreaking but the power it gives people when communities rally around to help is truly inspiring’.

These meanings attributed to voluntary giving are suggestive of what Clarke and Parsell (2022) refer to as ‘resurgent charity and the neoliberalizing social’. In referencing recent developments in the UK and other countries such as Australia and the US, they argue that both the mobilization of charity and welfare state restructuring need to be viewed as part of a ‘broader project to ‘reassemble the social’ in accordance with (neo)liberal ideals of spontaneous, affective, self-regulating sociality’. More than this, the attribution of these meanings is suggestive of how such attempts to enrol charity into the ‘neoliberalization of the social’ coalesce with the advancement of digital technologies and the promises of ‘bottom-up’ and decentralised forms of sociality they are proclaimed to afford.

While the dominance of such neoliberal visions of welfare is apparent in the body of texts we analysed, competing visions are also present. Of particular note are the gloomy and disapproving portrayals of people relying on charity due to inadequate government support, as illustrated by this Mirror article. Such accounts are marked by an attachment to a residual form of welfare associated with the post-war social democratic order. Somewhat conversely, we also see traces of a social democratic vision of welfare in more optimistic accounts of voluntary giving. For example a Guardian article praises the spirit of voluntarism and calls for a greater integration of ‘grassroots mutual aid’ into the NHS while also noting that it ‘will take more than neighbourliness to repair our weakened social safety net’.

This appeal to integrate mutual aid into the NHS chimes with the think tank New Local’s notion of ‘community power’, which is referenced in some of the articles we analysed. It’s a term that seems to be gaining traction in policy circles, with a range of people voicing its promises. In referencing the possibilities of a ‘digital innovation’, the conservative MP Danny Kruger calls for a ‘new paradigm’ whereby ‘community power replaces the dominance of remote public and private sector bureaucracies’. The commentator Hilary Cottom speaks of ‘community power’ in relation to a broader ‘community turn’ and her vision of a ‘Radical Way’. Such traction points to the degree of ambivalence that comes with this recent interest in ‘community power’. On one hand it opens up room to envision and create the kind of arrangements put forward in The Care Manifesto and experimented with in public-commons partnerships. On the other hand, much like ‘Big Society’, it becomes another way of legitimising welfare state retrenchment and constructing the social in ways that accord with neoliberal visions of self-governing and responsible citizens.

Our discourse analysis of newspaper articles only takes us so far in probing the ambivalent possibilities of this recent turn to community. As we now proceed with work package two (an affordance analysis of digital platforms) and work package three (interviews and participant observation with civil society groups), we will be able to develop a richer and fuller sense of how such dynamics are unfolding.

This blog is based on a paper presented at a workshop on ‘Communicating the wealth inequality challenge in hybrid media systems’ which was held from 5 – 6 October 2023 and was hosted by the International Inequalities Institute at the London School of Economics. I would like to thank the organisers and fellow attendees for their valuable feedback.